Battle of the Beverages: Will Coke Studio help Coca Cola slay the Pepsi dragon?

It is not often that a giant multinational corporation can be seen as an underdog, but the South Asian market for consumer goods is a peculiar space. In tobacco, the global number one is Philip Morris International, but in Pakistan and India, its smaller competitor – British American Tobacco – is dominant. And in beverages, Coca Cola may be the global colossus, but in this part of the world, it plays second fiddle to its rival PepsiCo.

The team at Coca Cola Pakistan, however, appears hell bent on changing that dynamic, and are willing to invest whatever it takes to gain market share in Pakistan’s large and rapidly growing market for beverages, particularly at a time when global food and beverage companies are struggling to grow market share in more developed, high-income markets.

“In developed markets, you can barely get single-digit growth,” said Fahad Qadir, the spokesperson for Coca Cola in Pakistan and Afghanistan, during an interview with Profit at the company’s main offices in the country in Lahore. “Pakistan is one of those countries which has double digit growth – sometimes even healthy double-digit growth – as far as the industry is concerned.”

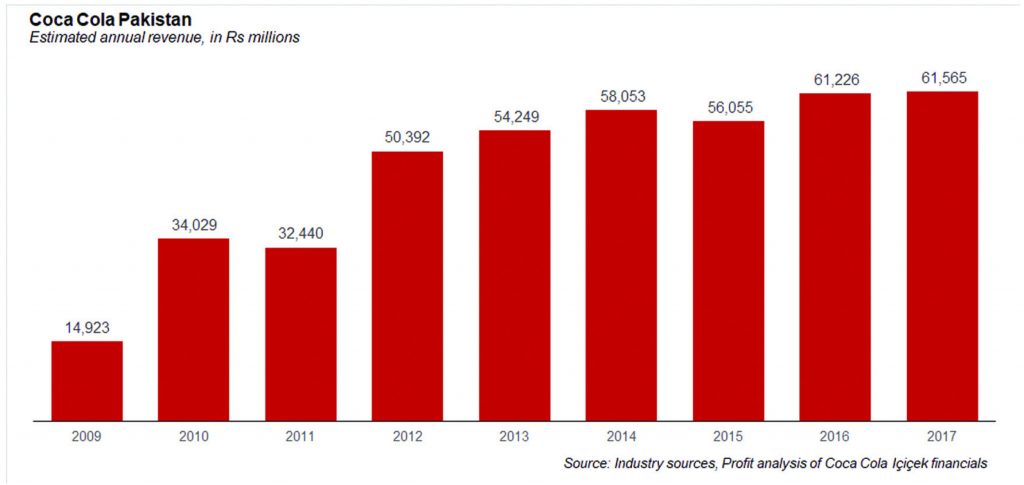

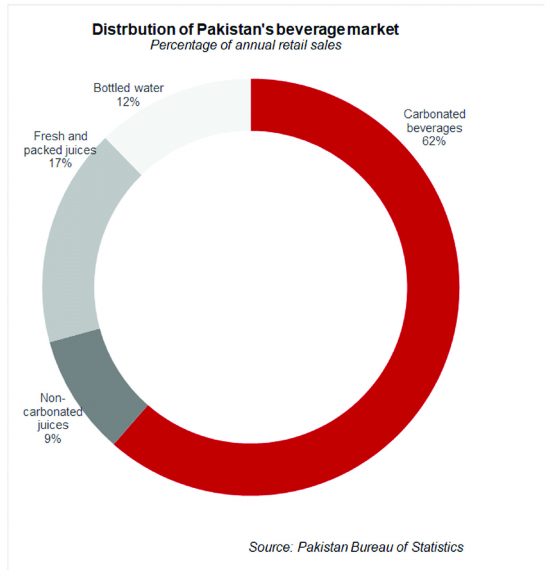

Qadir may be underselling just how rapidly the market has grown. Based on estimates compiled from industry sources, Profit estimates that the total retail value of beverages (carbonated, non-carbonated juices, and bottled water) sold in Pakistan hit Rs297 billion ($2.8 billion) in 2017 and has been growing at a rate of 15.9% per year for the past five years.

Of course, given the perennial challenges of electricity outages and infrastructure constraints, the actual amount earned by companies competing in this space is considerably lower. Again relying on those industry sources, Profit estimates that the total revenue of the industry as a whole was around Rs166 billion ($1.6 billion) in 2017. The difference between those two numbers is accounted for by the retailers’ margins, which are necessitated by the high cost of running power generators owing to daily power outages throughout most of the country.

The growth in the industry, incidentally, is driven almost entirely by growth in volume: the average Pakistani now consumes 26 litres a year of the beverages that Coca Cola sells, which includes not just its signature carbonated beverages, but also fruit juices (the Minute Maid brand) and bottled water (sold under the Dasani brand). That number has been growing at an average of 11.6% per year for the past five years.

Why Coca Cola is behind Pepsi

The carbonated beverage business was invented by the founders of what would eventually become the Coca Cola Company. Coca Cola was invented in 1886 by pharmacist John Stith Pemberton in Atlanta, Georgia, in the United States. The Coca-Cola formula and brand were bought in 1889 by Asa Griggs Candler, who incorporated The Coca-Cola Company in 1892.

Since then, the company has grown to become one of the largest in the world, and now owns over 350 brands and operates in 200 countries and territories around the world. Coca Cola operates in more countries than there are members of the United Nations.

PepsiCo, the market leader in Pakistan, has a slightly younger history, and operates in fewer countries than Coca Cola, and is smaller in revenue, despite having many more business lines than Coca Cola.

So how does PepsiCo dominate in Pakistan, and in South Asia more broadly?

Well, it helps to start first. PepsiCo entered the Pakistani market in 1979, when it entered into a partnership with Pakistan Bottlers, which was then a local bottling company that manufactured its own brand of beverages under the name Pakola.

PepsiCo then built out partnerships with seven other local bottlers throughout Pakistan and gained a commanding share of the Pakistani beverage market, easily beating out the British and Australian competitors who had existed in the country back then. It also made the strategically important decision to start sponsoring the Pakistan men’s national cricket team and frequently featured Pakistan’s favourite cricketer – Imran Khan – in its ads.

By the time Coca Cola even realized there was a market in Pakistan and began operations in the country in 1996, it was too late. PepsiCo had already been in the country for 17 years by that point, and had been the lead sponsor for the team that won the World Cup in Pakistan’s favourite sport.

Indeed, Pepsi’s ads almost invariably featured cricketers in Pakistan, starting with Imran Khan, but then moving on to Javed Miandad, and other great legends of Pakistani cricket, including and up to several members of the current international side.

Coca Cola initially tried to replicate the strategy that they believed had made PepsiCo successful: having eight, well-connected local bottlers handle the manufacturing and distribution of its products. But the formula proved too chaotic. Coca Cola was able to take some market share, but lagged far behind PepsiCo, which remained the dominant market leader in the country.

The Coca Cola structure and the 2008 shakeup

Before understanding how Coca Cola was able to put into effect its turnaround strategy, it is first necessary to understand the uniquely American structure of the company.

The Coca Cola Company owns the formula and the brand names of every Coca Cola product. In addition, it also owns the bottling company for its operations inside the United States. In most other countries in the world, however, the company retains ownership of only the brand the formula through a company called the Coca Cola Export Company.

In Pakistan, there is a local branch of the Coca Cola Export Company, not incorporated as a Pakistani company, but rather as the branch of a foreign company. That branch conducts all marketing and brand building activities and manufactures the concentrate for the company’s signature beverages from a plant it owns and operates in Raiwind.

When it first started operations, that concentrate used to be sold to eight separate bottlers who each had their own factories located throughout Pakistan. Within a few years of arriving in the country, however, it was clear that the business model of having several bottlers in one country was not working, so the company spent a decade buying out every single one of its bottling partners, and by 2008, had consolidated them into one single company called Coca Cola Beverages Pakistan.

For some time, Coca Cola Beverages Pakistan was a wholly-owned subsidiary of The Coca Cola Company in the United States, but in 2008, the US-based parent sold a 49% share to Coca Cola Içiçek, a Turkey-based partner of the group. Coca Cola Beverages Pakistan operates six bottling factories in Pakistan, located in Karachi, Gujranwala, Multan, Lahore, Rahimyar Khan, and Faisalabad.

It was then that Coca Cola began its most ambitious project of building up its brand to compete against the powerful brand identity that PepsiCo had built up in the country. Only after consolidating its operations, and overcoming the logistical and operational challenges it had previously faced, was it able to focus on the strategic task of building up its brand identity in a country that had long ago been conceded to its main rival in the global market.

Coke Studio and the takeoff

The mistake that Coca Cola made was in assuming that giving out bottling licences to politically well-connected families – which is what PepsiCo had done – was the reason for PepsiCo’s success in Pakistan and the only formula for success in the Pakistani market.

In hindsight, of course, this was not true. Aside from having a head start in the Pakistani market, PepsiCo invested in building an association with the one thing that the overwhelming majority of Pakistanis felt an emotional attachment to: the men’s national cricket team.

By associating itself with the stars that young Pakistanis looked up to – Imran Khan, Javed Miandad, Wasim Akram, Shahid Afridi, etc – PepsiCo made itself into an almost local brand. Many foreign brands are often the subject of conspiracy theories, and PepsiCo certainly had its fair share of such theories about its brands, but by being seen as the supporters of a nationally unifying institution – Pakistan cricket – PepsiCo were able to overcome what may otherwise have been a significant challenge and build a commanding lead in market share.

If Coca Cola was going to succeed in the Pakistani market, it was going to have to take on that branding advantage.

Enter Rohail Hayat.

Rohail Hayat was formerly a member of something that had been a Pakistani institution itself: the pop music band Vital Signs. In 2008, he was given charge by Coca Cola to create something for the Pakistani audience that had already been tried by the company in the Brazilian market: a platform for musical performances aired on a studio to a television audience commercial-free. The goal would be to create the sound of Pakistan, blending folk music with modern, established stars with young up and comers, Urdu singers and local language stars.

Coca Cola may not have realized it at the time, but this was exactly what they were looking for.

If Pepsi had cornered the market for inspiration by linking itself with the Pakistani cricket team, Coca Cola could respond by taking up the task of sponsoring soulful, uplifting music.

The show started in 2008 and was almost immediately a success. “The popularity of Coke Studio is far greater. We get hits from almost 180 countries in the world on our official pages. A number of our songs have crossed 10 million, 20 million and even 100 million hits on YouTube,” said Qadir.

So big a success was Coke Studio Pakistan that Coca Cola began replicating the formula in other countries. In 2011, Coca Cola introduce Coke Studio India, produced in partnership with MTV. The idea was then also adapted for Arab audiences with the 2012 launch of Coke Studio بالعربي.

It was success like no other multinational corporation’s ad campaign had ever gotten in Pakistan. Coke Studio may have originated in Brazil, but it died out there very quickly. It was in Pakistan that it found success, and it was the Pakistani model that Coca Cola successfully exported to other parts of the world, a fact that Pakistanis have begun to take pride in, which certainly helps the company build its brand in the country.

“Coke Studio produces the recognition, the recall, the brand, the preference, the choice and the consumption and everything goes up,” said Qadir. “The standing and the equity of the brand has increased considerably in all these years. Coke Studio has been the cornerstone of our success story in the last 10 to 12 years. It has not just become the identity of Pakistan, it is the identity of every Pakistani and what Coca Cola stands for locally and internationally.”

The numbers certainly bear out Qadir’s claim. In 2008, the year Coke Studio started, Coca Cola’s share in the Pakistani beverage market was around 26.3%, a number that has since jumped sharply to 37% at the end of 2017.

In an extension of the connection between the Coca Cola brand and Pakistani music, the company launched Coke Fest in 2017, a series of outdoor festivals across major Pakistani cities with several food stall and live music performances.

“It gives a different dimension to what the brand is doing,” said Qadir. “There are not many opportunities people have of getting to enjoy outdoor music. So we came up with Coke Fest. We have 30,000 to 40,000 people attending every event in every city that we go to. I think this provides an opportunity for people to go out with their families and enjoy. Yes it is an off shot of the music activities we do, but it is becoming a strong pillar of the marketing activities we do every year. Eventually everything has to result into more sales and more beverages selling for the company.”

Investing in operational capacity

Brand building, however, is not enough, a lesson far too many brand managers have a tendency to forget. Coca Cola has been investing heavily in building out its capacity to manufacture and distribute its products to the market.

In 2011, Coca Cola invested $172 million into Pakistan to manufacture aluminum cans for Coke. The product had previously been imported from the Middle East, which rendered its price too high to be competitive in the Pakistani market.

In 2013 and 2014, it invested a further $248 million into the Pakistani market in order to build two new bottling plants in Karachi and Multan, in addition to the plants that had already existed in both of those cities, as well as investing in more coolers, which the company distributed amongst retailers to help boost the company’s retail sales.

Given the infrastructure challenges and daily power outages in Pakistan, it is common not just for large multinational food and beverage companies, but also many other types of companies, to distribute coolers, refrigerators, freezers, and even diesel generators to retailers to help keep their products at the optimal temperature for the consumption of the end-consumer.

And the company is now planning to invest another $250 million over the next two years to continue that expansion spree.

“We are putting in a new greenfield plants,” said Qadir. “We just inaugurated our Faisalabad greenfield. A couple of years ago, we inaugurated Multan, so we are putting up new greenfields every two to three years, which will help our distribution and of course our production capacity. We are investing $250 million in the coming few years and we invested the same amount in the last two to three years.”

That continued investment in production and distribution capacity is a necessary outgrowth of the company’s aggressive marketing campaigns. After all, what good is a marketing campaign that persuades more people to buy your product if you are not able to produce enough of that product to get to the people who are now willing to spend money on it?

Part of the increase in capacity has been the introduction of new brands, such as Dasani water, the company’s flagship bottled water brand, which has supplanted Kinley as its main bottled water offering in the Pakistani market. “Kinley was the first water brand we launched in Pakistan. When you look at the business plans every year, you do look for new innovations. So from that perspective we thought that we will switch to Dassani, in order to revitalise the portfolio. We have redesigned everything. Right from the shape of the bottle to the labelling. Switching over has been good and the feedback has been great,” said Qadir.

The taxation problem

The one consistent complaint Coca Cola has had in Pakistan is the taxation regime it faces, both in terms of the actual rates it is legally required to pay – which the company claims are too high – and the enforcement mechanism, which the company feels is too lax and thus discriminates against companies that actually pay their taxes versus less scrupulous players who avoid taxes and thus have more cash available to reinvest in their business.

“The entire beverage industry is being very disproportionately taxed,” said Qadir. “We pay excise duty on top of the sales tax. No other segment within food and beverages pays excise duty, so beverage industry is the only one doing that. It increases our cost to do business. Excise duty in Pakistan is the second highest in the region including China, India and Indonesia which means that we don’t have much space to grow, despite the fact that we are bringing in a lot of investment which runs into hundreds of millions of dollars.”

“We feel pride in saying that we pay our fair share of taxes,” said Qadir. “But sometimes tax payments of other local players is questionable. We don’t want anyone getting an unfair advantage from one side and using that money to fuel growth for themselves.”

What comes next?

Yet despite the supposed disadvantages to investing in Pakistan, Coca Cola continues to pour money into the economy. Part of it has to do with the fact that Coca Cola Içiçek, the publicly listed Turkish company that owns half of, and operates, Coca Cola Beverages Pakistan has reached a market saturation point in its home market of Turkey.

Coca Cola Içiçek operates in several markets across the world, including Azerbaijan, Iraq, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Pakistan, Syria, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Jordan. None of those markets, however, have either the size or the rapid growth that the company has been able to achieve in the Pakistani market.

As a result, the management of Coca Cola Içiçek continues to speak glowingly of Pakistan and its prospects for growth and will likely continue to invest aggressively in the country for the foreseeable future.

“In Pakistan, we have primarily focused on achieving profitable volume growth through pricing and effective discount management, which resulted in a significant improvement in operational profitability. Brand Coca-Cola, with the highest brand love score globally, outperformed the sparkling category and was more than double the nearest competitor in Pakistan. That means greater production of existing brands, as well as the constant introduction of new brands into Pakistan, including some of Coca Cola’s biggest global brands,” said Burak Başarır, CEO of Coca Cola Içiçek, in his 2017 annual letter to shareholders.

“We have expanded our portfolio. We are into juices now. We didn’t use to be in that before. And we launched energy drinks like Monster,” said Qadir. “We just make sure that we produce the best beverages and we deliver them wherever possible. It is still a long way to go but I think we are happy with the performance that we have so far.

Courtesy: Pakistan Today.